Heritage revitalization faces hurdles

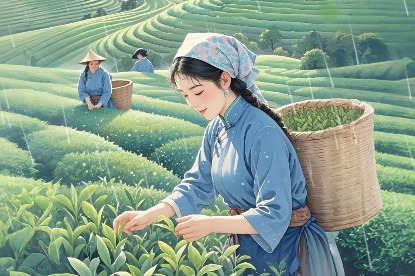

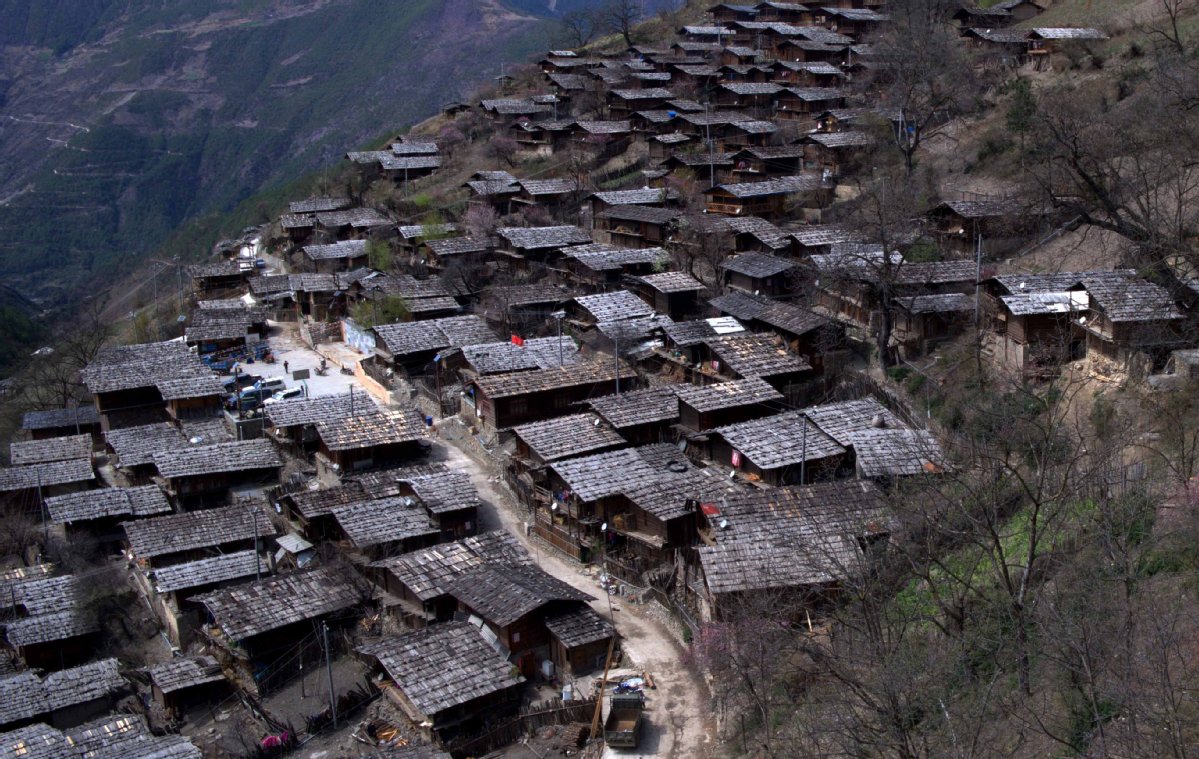

Traditional skills can help lift rural villagers out of poverty, but better infrastructure is needed, Cheng Si reports from Diqing, Yunnan.

At their black pottery workshop in the town of Nixi, in Yunnan province's Diqing Tibetan autonomous prefecture, the father and son were arguing again.

The time-honored pottery-making technique, handed down for more than 1,800 years, was put on the list of State-level intangible cultural heritage in 2008.

Most of the villagers rely on the traditional craft for their livelihoods, and Losang Shepa, 26, wants to modernize production to widen its appeal. His father, Dadrin Pheldub, 46, has agreed to experiment with an electric kiln but is not in favor of producing nontraditional items.

"It's a waste of time! Why did you do this useless work rather than making it into a traditional Tibetan bowl for butter tea?" he scolded his son, who wanted to shape the clay into a modern coffee cup.

Sighing, Losang Shepa said: "My father, like many other senior craftsmen in the village, is conservative when it comes to handing down the skills. It's like having a precious jewel with great economic value held tightly in your arms, but nobody even spares a glance at it because of its strange appearance."

There are 11 steps involved in making black pottery, including collecting the clay, shaping it and airing the pottery. The best-known black pottery product, according to Losang Shepa, is a pot for stewing chicken, which usually takes 10 to 15 days to finish as airing the clay requires good weather conditions.

Losang Shepa said he is convinced black pottery has a promising future, but he is still concerned about its development.

"We want to develop rural tourism by attracting travelers with our traditional skills," he said. "However, the product we offer is hardly appealing to tourists' taste. We still have a long way to go to revitalize the heritage to help develop the tourism industry and bring more villagers out of poverty."