Russians opt for hope over hardship

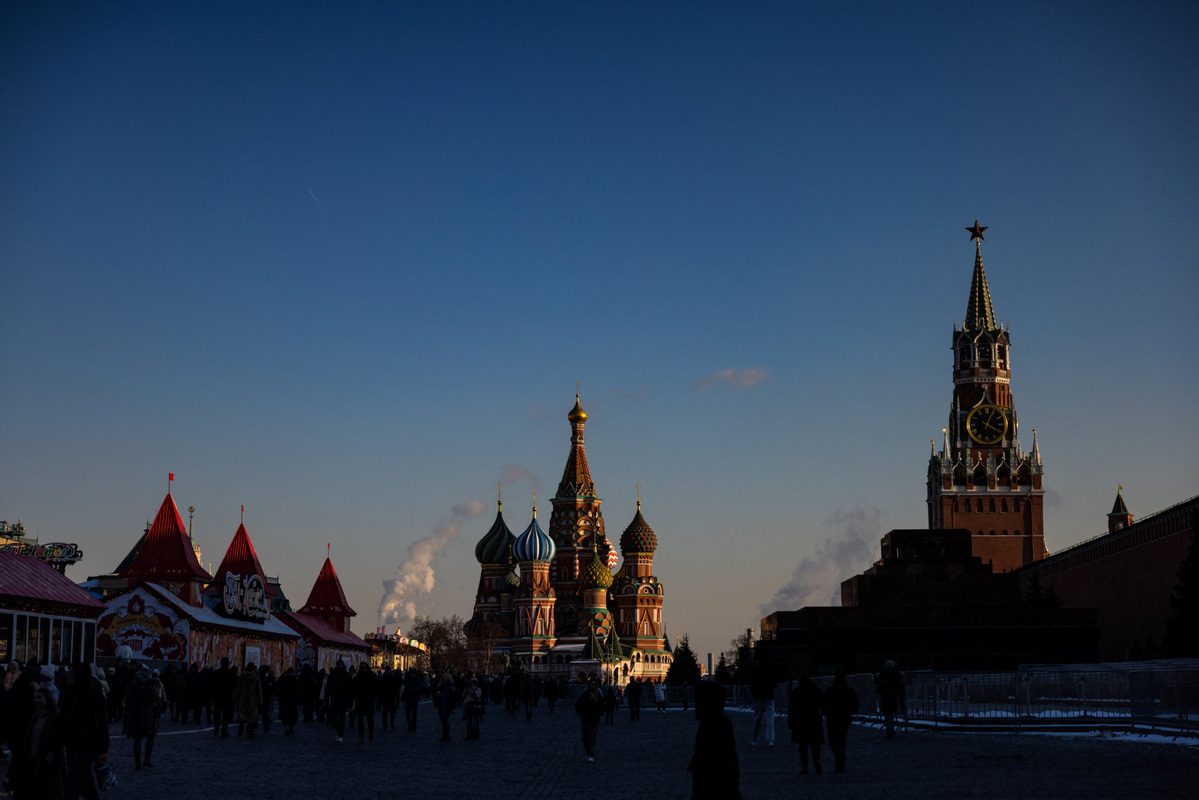

The atmosphere brought about by the New Year decorations in Russia for 2025 feels noticeably different from what I observed years ago.

I still remember December 2022. Alongside the traditional tall fir trees, giant Zs and Vs stood prominently — symbols of victory for the country's special military operation in Ukraine, which began on Feb 24 that year. This year, however, there are no Zs, no Vs, and no slogans at Moscow's main gatherings, as the conflict enters its fourth year.

A similar shift is evident in parts of Central Russia's Siberia. Two years ago in Chita, towering ice sculptures of Russian soldiers clutching Kalashnikov rifles stood among the New Year and Orthodox Christmas decorations. This year, such displays are absent — replaced by snow figures.

Among the Russians I've met and stayed in touch with over my seven years in the country, more now prefer to avoid reminders of military conflicts, both within Russia and along its border with Ukraine.

In the heart of Moscow, retired schoolteacher Tatiana Ivanovna sits on a park bench. Her voice, though soft, carries the weight of years of wisdom — and a yearning for peace.

"We have seen enough suffering. The world needs to stop fighting. As ordinary people, we just want to live our lives, raise our children, and not worry about tomorrow," she says.

Tatiana's words reflect a growing sentiment among everyday Russians: a deep desire for peace amid global tensions. As I traveled through Moscow, St. Petersburg, and smaller towns, I noticed a common thread — a longing for stability and harmony.

According to a recent survey by Russian pollster Levada Center, more than 60 percent of Russians favor peaceful resolutions to international disputes. While patriotism remains strong, there is an increasing awareness of the human and economic costs of prolonged tensions.

Sanctions have hit hard, particularly for the middle and lower classes. Since 2022, Western countries have imposed multiple rounds of sanctions on Russia, prompting the Russian government to respond with countermeasures — banning imports of many food products, including fruit, dairy, and meat, from the United States, the European Union, and other nations.

At the time, officials framed these restrictions as an opportunity to strengthen Russia's agricultural sector and achieve food self-sufficiency. To some extent, the strategy has worked. Domestic agricultural production has expanded, making Russia one of the world's largest wheat exporters.

Even after years of sanctions, supermarket shelves remain well-stocked, filled with Russian-made cheeses, sausages, and other products that were once imported. However, this shift has come at a cost.

For the majority of ordinary families, affordability has become a problem. Last year, the price of potatoes went up by 88 percent, while butter rose by 35 percent. In some places, butter is placed in security boxes as theft becomes increasingly common.

"Russian agriculture has grown, but it's not always efficient," says economist Oleg Sokolov. "The lack of competition from foreign producers has allowed domestic companies to raise prices without significantly improving quality. Add inflation and logistical challenges, and you get the situation we have today — food is available, but it's expensive."

Olga Grigorieva, an office worker in Yaroslavl, says she used to buy French cheese and Italian wine. Now, she struggles to afford basic groceries.

"I hope the fight will end. That's the most important thing," she says. "Then, everything will get back on the right track."