Getting world drawn to China

UK archaeologist explores nation's development via ceramics, jades

Language of objects

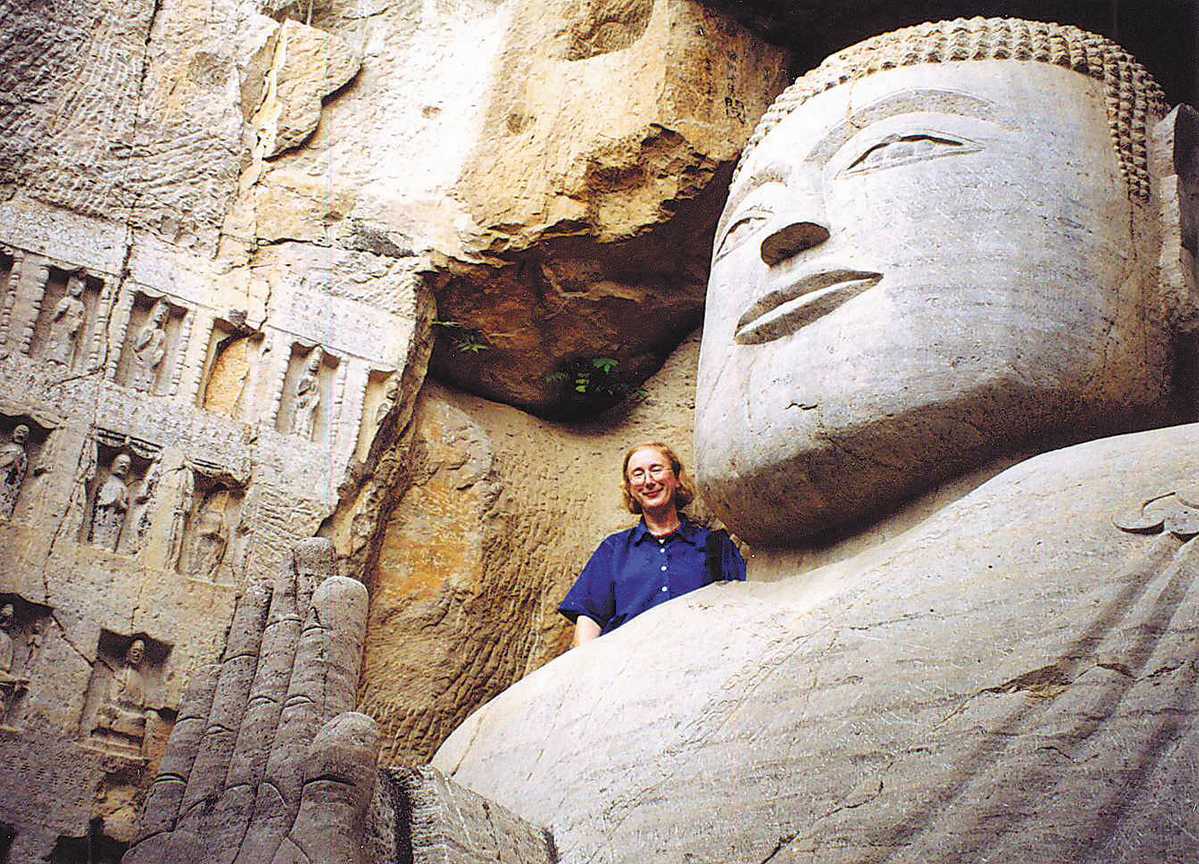

In 1968, when Rawson joined the British Museum, she was tasked with cataloging probably thousands of ceramics and jades from the Shang, Zhou (c. 16th century–771 BC), and Han (206 BC–220 AD) dynasties — relics she found "very surprising" at first sight.

Seeing some objects as "China's greatest works of art", Rawson found that those exquisite things are often not vehicles for self-expression but functional forms for ancestor worship, crafted according to strict standards dictating their shapes, patterns, and decorations, exemplified by bronze vessels.

She wondered why the Chinese are so obsessed with this particular type of object, but not gold or gems?

Breaking it down step by step, what stands out to Rawson is that the ancients' fascination with bronze vessels reveals the distinctiveness of China, from its climate and terrain to the cosmology of the inhabitants.

The Loess Plateau in north-central China once buried the ores or metals under layers of heavy wind-blown dust. The mining alone required an immense workforce, not to mention the demanding craftsmanship needed to smelt and cast even a single piece, which explains why bronze vessels were mostly evacuated from the tombs of royalty and nobility, Rawson says.

Life and afterlife

"But why bury them," she asked herself. "The bronzes are immensely valuable. They take a great deal of metal; they take a huge scale of workmanship and artistry."

"That is because the Chinese, I think, today still believe that the people, after death, go on living the life they lived in life. This is a feature of Chinese culture which took me many decades to learn."

Just like the Terracotta Warriors, who stand guard near the mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang to protect the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), all sorts of grave goods were provided for the ancestors to ensure a privileged afterlife.

Meanwhile, the descendants, by practicing ancestor worship or making ritual offerings, prayed for blessings for the living.

Life and the afterlife in China unveil fundamental differences in the nation's ancient society, in how the ancestors were treated as being at the top of a generational hierarchy, and how families, united by shared ancestry and kinship ties, became central, Rawson says.

In her latest book, Life and Afterlife in Ancient China, she explores 12 grand tombs and a major sacrificial deposit from across China.

The "master interpreter", as the former Director of the National Gallery in London and British Museum Neil MacGregor describes Rawson, never treats an object in isolation but traces down to the usage, customs, and beliefs — shaped by climate and geology — all pointing to why the Chinese are not like Westerners or anyone else in the world.

While China is fascinated with bronze, the West prizes gold and gems. While the Chinese eat rice from ceramic bowls, the West uses plates for salad. What Rawson believes is that every culture develops its material system.

"My Chinese students are always horrified when I say, 'Let's have salad,'" she says. "Differences hit us every day, all the time. I found that being specific. That's why I go for objects, for food, perhaps later for dress to emphasize that everyday life is different."

The language of objects had, sometimes, been omitted by the early documents, and those abundant transmitted writings were often not contemporary with the events they describe, Rawson notes.

Now, there is someone who gives a voice to the objects.