'Chinese wave' already impacting the world

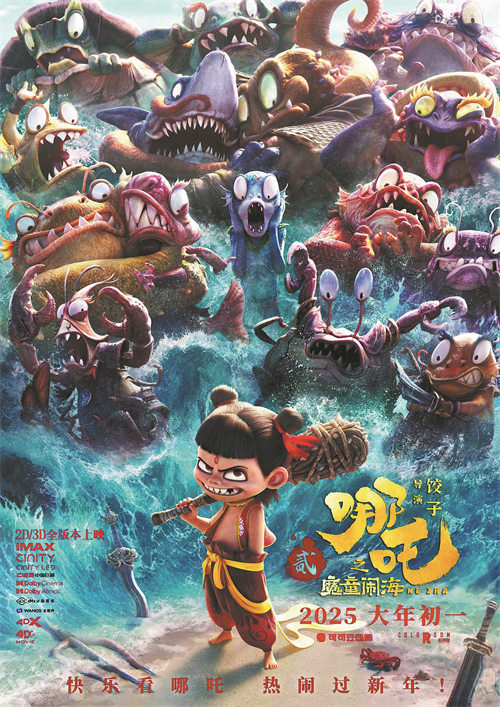

Ne Zha 2 has become the highest-grossing animation film of all time, earning more than Disney's Star Wars: The Force Awakens at the box office.

But the Chinese film industry should not bask in the glory of Ne Zha 2 for too long and become complacent. It should dream bigger, aim higher and achieve more remarkable goals.

Before I continue, let me make clear I do not seek to diminish the value of our own culture while praising other cultures; rather I seek to learn from other cultures' successful experiences, and better understand both ourselves and them.

In January 2025, the Oxford English Dictionary included a batch of newly adopted words, among which seven were transliterations from Korean. These terms, arranged alphabetically, are: dalgona (a type of caramelized sugar candy), hyung (a term used by younger men to address older men), jjigae (a Korean stew), maknae (the youngest member in a family or group, now specifically denoting the youngest member of a K-pop group), noraebang (a Korean-style karaoke room), pansori (a traditional Korean narrative singing genre) and tteokbokki (spicy stir-fried rice cakes).

The phenomenon of culturally specific concepts being adopted into another language through transliteration is a well-documented aspect of cross-linguistic borrowing. But the inclusion of Korean kinship terms such as hyung and maknae in the OED, considered a linguistic authority, is noteworthy. These terms, deeply embedded in the Korean social structure, have transcended their original cultural context to become part of the global English lexicon.

Besides, the inclusion of "jjigae" and "noraebang" in the OED, despite the existence of English equivalents like "stew" and "KTV", underscores the cultural importance and specificity these terms carry.

The recent wave of Korean terms being accepted into the English language, though modest in size, follows a much larger influx in September 2021, when the OED added 26 Korean words, which included three kinship terms: noona (used by men to address older women), oppa (used by women to address older men) and unni (used by women to address older women). The inclusion of such terms highlights the growing influence of popular Korean culture, particularly K-pop and K-dramas, on global linguistic practices.

To contextualize this phenomenon, consider the hypothetical scenario of Chinese kinship terms like ge (older brother), jie (older sister), shu (uncle) and yi (aunt) being adopted into English. Given the existence of English equivalents such as elder brother, elder sister, uncle and aunt, the use of transliterated Chinese terms would likely provoke skepticism and criticism.

The 2021 OED update featured a diverse array of Korean-derived terms, including K-drama (Korean TV dramas), Konglish (Korean English), Korean wave (a direct translation of hallyu), mukbang (eating broadcast), Taekwondo (a Korean martial art), and trot (a genre of Korean music). Their inclusion reflects the global reach of Korean cultural exports, from cuisine and entertainment to lifestyle and language.

The integration of these terms into the English language is not merely a linguistic curiosity but a testament to the soft power of Korean culture. Since the 1990s, the Republic of Korea's cultural industry has leveraged state support to propel the Korean wave, influencing global trends in music, television, fashion and cuisine. English, as a global lingua franca, has absorbed these cultural terms, reflecting the dynamic interplay between language and cultural power.

English has far more Chinese-derived words than Korean-derived ones. But we are yet to see a surge of Chinese-derived terms being integrated into the English language. This suggests certain languages exert greater influence on global lexicons under certain conditions. The success of Korean cultural exports, coupled with their strategic branding and global appeal, has facilitated this linguistic exchange.

The recent success of Chinese cultural products, such as Ne Zha 2, demonstrates the potential of Chinese culture to similarly resonate globally. But realizing this potential requires sustained efforts to promote Chinese cultural narratives and linguistic elements on the international stage. By fostering an environment conducive to cultural exchanges, Chinese-derived terms could one day enter the English lexicon in waves, much like their Korean counterparts.

By analyzing the phenomenon of Korean terms' influx into the English language, we gain valuable insights into the mechanisms of linguistic borrowing and the role of soft power in shaping global communication. The challenge lies in harnessing cultural and linguistic assets to foster mutual understanding and appreciation in an increasingly interconnected world.

Let us open our minds and embrace both incoming and outgoing cultural exchanges. By learning from the strengths of others to improve ourselves, we can achieve higher goals. Till then, the Chinese wave will surely take Chinese elements to and keep influencing the global stage.

The author is dean of the School of Foreign Languages at Sanda University in Shanghai.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.