The maker of miniature worlds

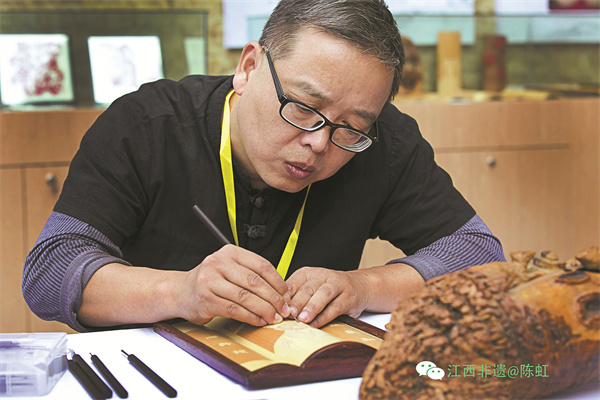

Hakka bamboo artisan carves space for ancient art in modern life, Yang Feiyue reports.

The slender bamboo panel almost seems to breathe under the ingenious ministrations of Guo Yingxiong's knife.

In his workshop in the Zhanggong district of Ganzhou, Jiangxi province, the 58-year-old conjures worlds that erase time, in which rivers flow eternally, the current rendered so delicately that it almost shimmers with actual movement. An ancient bridge arches over the river, carrying the rhythms of daily life unfolding on a bamboo sheet — a tea peddler's weathered face glistens as he adjusts his shoulder pole, an elderly man navigates wooden planks on his bicycle, and young lovers sit entwined on the bridge's edge, their silhouettes backlit by the sun that stains the river the color of molten copper.

Peering closer at this miniature world, you will notice the gnarled roots of a banyan tree clutching the riverbank, and the bridge's lineage traced in vermilion calligraphy.

"I try to let the material speak for itself," Guo says.

And so the natural russet streaks of bamboo skin are shaped into sunset clouds, a knothole becomes the moon reflected in the river, while the fibrous texture is used to mimic both the bridge's wood grain, and the water's rippling surface.

For more than four decades, Guo has been a living bridge between the ancient art of Hakka bamboo carving and the modern world. His hands, ridged with calluses and scored by decades of nicks, tell the story of an art form that once graced the studies of Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) scholars.