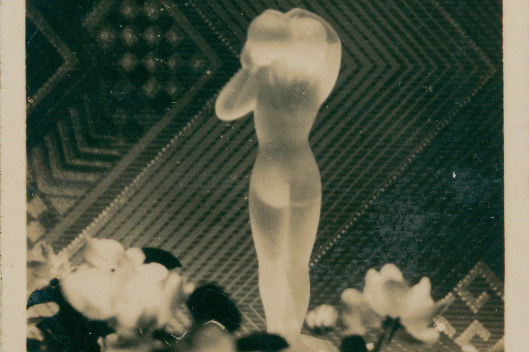

Vase offers a glimpse of intrigue

Chinese artwork in Bulgaria, with intricate decorations, suggests creative genius and a capacity to forge connections across borders, Yang Feiyue reports.

One such work, a plate titled Picking Tea and Catching Butterflies, was selected for exhibition in Eastern Europe in 1954, according to the Wang Xiliang Chronology. Archival records show that this piece was among a batch chosen for a touring exhibition organized by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and the Beijing-based Central Academy of Fine Arts.

"This porcelain vase may well be one of those pieces," Lian says.

Beyond its cultural and historical implications, the vase also stands as a narrative and visual triumph. It breathes new life into Chinese folktale The Legend of the White Snake, transforming it into a four-panel pictorial epic that seamlessly blends classical artistry with modern storytelling.

The legend recounts the tale of Bai Suzhen, a benevolent snake spirit who transforms into a woman to repay a debt of gratitude to a mortal, Xu Xian.

Their love blossoms into marriage, but they are later torn apart by the zealous monk Fa Hai, who exposes Bai's supernatural identity and imprisons her beneath the Leifeng Pagoda. Her loyal maidservant, Xiaoqing — a green snake spirit — and later their son seek to free her.

Popularized through operas during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing dynasties, it remains a timeless allegory.

Wang rendered each character with exquisite detail and symbolic meaning.

The bearded monk Fa Hai dominates the composition, wearing a five-Buddha crown and a crimson monastic robe fastened with circular knot buttons over a yellow undergarment, exuding stern doctrinal authority.

Wang's brush captures the character's dogmatism through facial rigor, which highlights thunderous brows and eyes brimming with righteous fury, Lian notes.

Bai Suzhen appears with her right hand resting on a sword. Her defiant stance is emphasized through her jade-green cloak and cloud-collar drapes, layered over a tortoiseshell-patterned warrior sash — a fusion that implies both grace and combatreadiness.

Her maidservant, Xiaoqing, dressed in azure, is a symbol of purity and rebellion. She is depicted midmotion, wielding a back-slung sword with red ribbons trailing across her yellow-trimmed robes.

"It is noteworthy that Wang incorporated his physical traits into the portrayal of Xu Xian, adding a special touch of the artist's presence to the traditional iconography," Lian observes.

The vase entered the museum's collection sometime after 1965. While its exact path remains unclear, scholars believe it likely traveled as part of a touring exhibition or was presented as a diplomatic gift to Bulgaria and the city of Plovdiv during the wave of cultural exchanges among socialist nations after World War II.

"The vase's provenance demonstrates the international recognition of Wang's artistry and offers valuable insight into the cultural exchanges in the mid-20th century," Lian adds.

Lian's further research also led him to related collections at Sofia's National Gallery in Bulgaria, where he found works by other prominent Chinese artists such as He Xiangning (1878-1972) and Xu Beihong (1895-1953).

They all suggested a robust web of cultural diplomacy, Lian says.

Contact the writer at yangfeiyue@chinadaily.com.cn